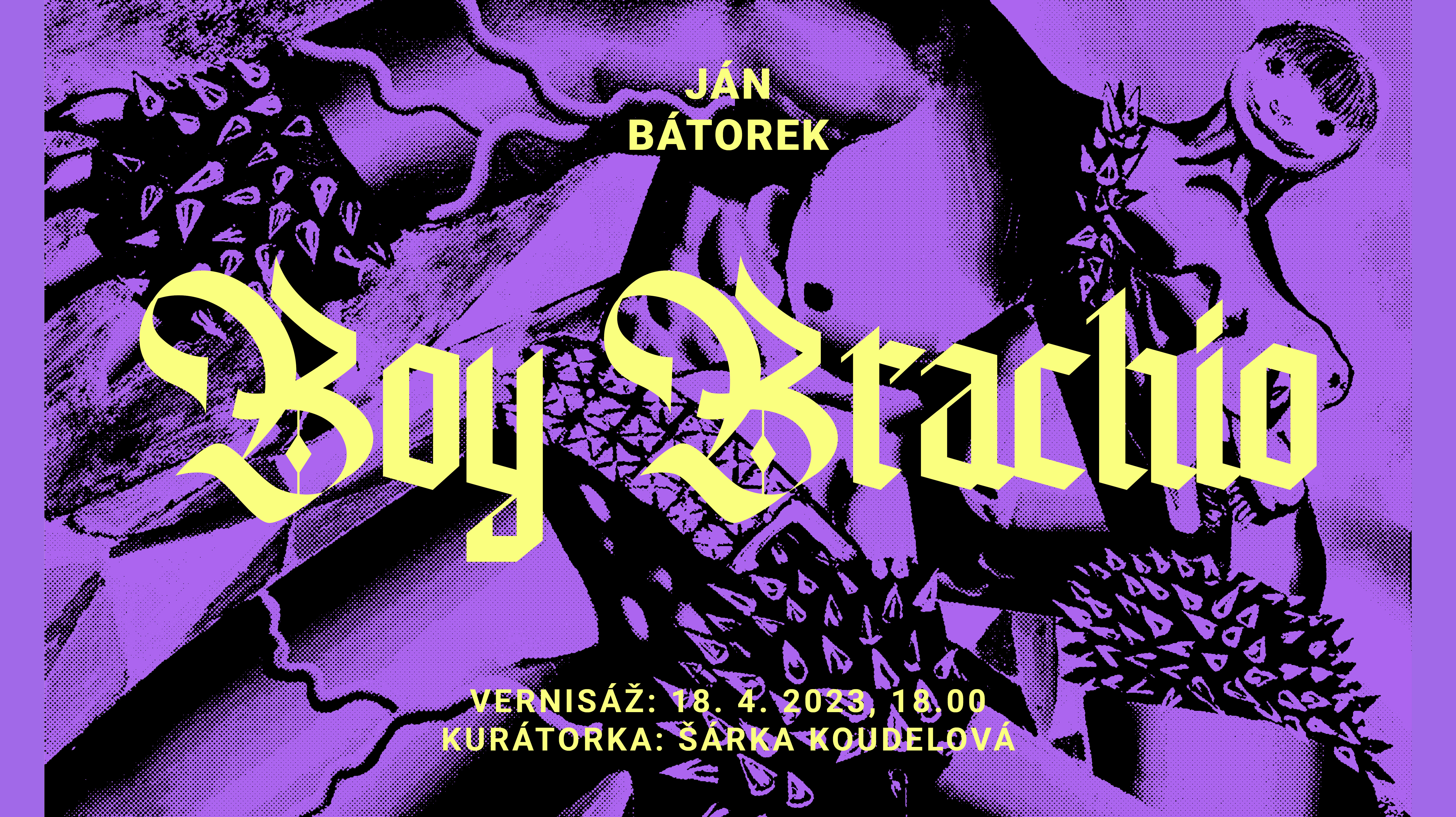

Ján Bátorek: Boy Brachio

BUNKERER

SORGE

EVA PORATING

SODA

exhibition: 19 April – 9 May, 2023

Legend has it that when the monastic brothers prepared the body of St. Andrew Zorard for burial, they discovered that he wore a chain that had long since grown into his skin. The saint, who voluntarily lived an ascetic life, inhabited the thorny hollow of a tree, and wore a “crown” he had made himself, with rocks suspended off it, which would prevent his weary head from resting even at night. The overtight chain is also the detail on Ján Bátorek’s small-scale painting. The painting is part of a loose series called Devon, the central motif of which is the palm tree, a reference to prehistoric times, or, rather, to our roots. Bátorek himself uses a Zorard-like chain to bind himself to his own roots. The palm trees and anthropomorphic heroes that populate his paintings are often adorned with the thorny attributes of punk and metal subculture, evoking both Zorard’s self-harming struggle with the lightness of being and the nihilism of a youth disillusioned by society. The romantic suffering of coming of age on a 1990s housing estate, where the grey curtain of pre-revolutionary times met the oppressively unbridled possibilities and flamboyant colours arriving from the West, is an archetype for the scenography of the small dramas inside Bátorek’s paintings. During the course of his artistic endeavours, the artist practically maps out the development of his sources of inspiration – recently, the heroes of his paintings included Ferda Mravenec (Ferdy the Ant; a Czech literary and comics character – translator’s note) inserted into situations or quotations from the history of art that were important to the artist, e.g. as Saturn devouring his son – a larva. This series of paintings even earned Bátorek a mention in a monograph on Zorard*, where he is listed as one of the artists working with Zorard’s legacy in a contemporary context.

The exhibition Boy Brachio presents a gripping series of paintings that naturally follows on from his introspective exploration of one of his first literary heroes. In his present paintings, the artist identifies with the brachiosaurus, whose appearance and attitude to life were born through a cross-breeding of Karel Zeman’s legendary 1995 film, Cesta do pravěku (Journey to the Beginning of Time) and formally overstated dinosaurs found on stickers from “Western” chewing gum. Bátorek thus combines a tendency towards lyrical composition featuring a low sky with the exaggerated, veiny muscles and warlike body language worthy of a superhero. The setting of a housing estate in Kysuce that is constantly cloudy or rainy, home to the lower middle class, easily suffering under both the old and succeeding regimes of the late 1980s/early 1990s, is a desolate environment reminiscent of Nick Cave, where the only positive possibilities are drugs and unhappy loves.

In his newest series, Ján Bátorek confronts his own origins, childhood, and maturation; the challenges and futilities of his generation. He attempts to come to terms with the bigoted and nationalist elements in Slovak society, the disappointment in the reality of the desired utopian freedom, and his own fatherhood. Visually, he confronts both the legacy of romantic books and lyrical illustrations that were once typical of our region, and the challenge of digital transitions and structures. His work thus forms part of a striking stream in Central European painting to which we could also append the colour-reductive approaches of Ondřej Basjuk (CZ), Julius Hofmann (DE), and Pavel Matyska (CZ). These paintings by men born in the 1980s that refer to prehistory, the history of art, boyhood adventures, and societal problems are characteristic in their ironic perspective on the past and skeptical view of the future. They are metaphors of the desire for sharing, difficult to formulate under society’s notions about what the appropriate forms of masculinity are. They are a dark disillusionment as well as a joyful bromance; a relationship based on a sense of emotional belonging conditioned by a joint fascination with pop-culture idols.

[*] Tomáš Prokůpek et al., Ondřej Sekora – Mravenčí a jiné práce, published by the Moravian Museum in Brno in 2019, pp. 257–258