-

30. 10. 2019Rezident

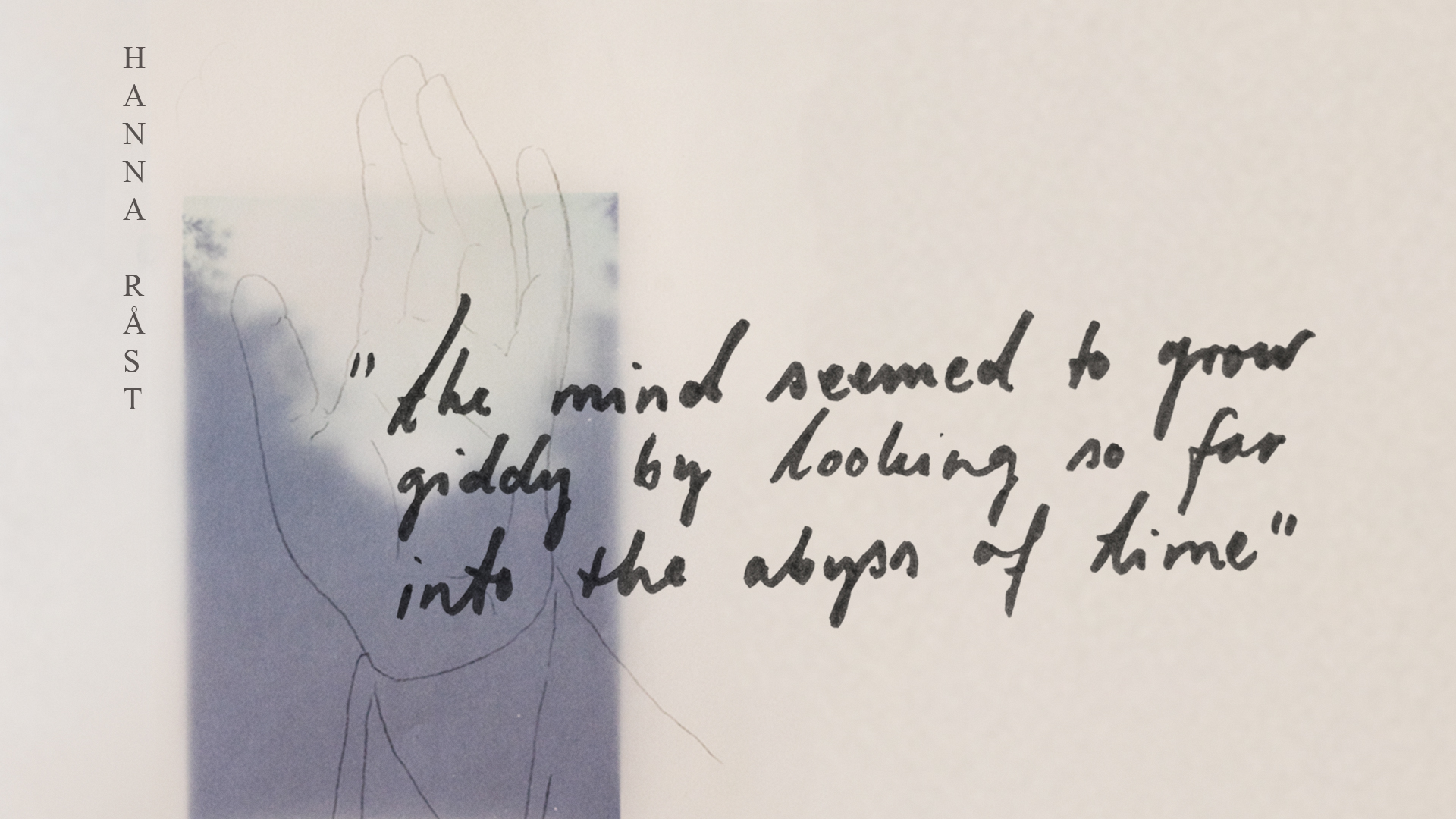

Hanna Råst (FIN): The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.

We cordially invite to the exhibition of the Finnish resident Hanna Råst, who has spent almost two months as an artist-in-residence at Studio PRÁM. Through her stay she has focused on the media of photography. She is mostly interested in what kind of shapes and forms can the photographic material take.

In collaboration with curator Šárka Koudelová they have prepared the exhibition called “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.” The opening of the exhibition is on October 22nd, 2019 at 7pm at Studio PRÁM and the exhibition is to be seen till October 30th, 2019.

“What clearer evidence could we have about the different formation of these rocks, and the long interval which separated their formation, had we actually seen them emerging from the bosom of the deep?… The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so deep into the abyss of time.” This quotation from the works of James Hutton perfectly represents the creative approach of the Finnish artist Hanna Råst (1986) in the way it paradoxically combines the scientific and the lyrical attitude. The versatile Scottish chemist, philosopher, physicist and, above all, geologist James Hutton lived in the 18th century, and thanks to his theory that the same geological processes which were happening on Earth “before mankind” are still occurring today, he is often referred to as the “Father of Modern Geology”. Thus, if we can examine a certain process in the present, it is likely that it was also acting upon the origin of the objects that surround us. These perceived objects have inevitably changed their appearance and properties over time – yet do they still carry the spark of the moment of their origin? And do we, only able to experience time to such a limited extent, even have the capacity to look upon their primary image in the purity of its birth?

The earliest known surviving photograph of a real-life scene is thought to be the View from the Window at Le Gras, taken by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. This heliographic image needed at least 8 hours of natural light to be exposed. Even after being soon replaced by the invention of the much faster daguerreotype, the view of the roofs from Niépce’s window survived its author and authors of the inventions to follow, and those eight hours of light can still project the uniqueness of the original image on our retina.

Hanna Råst intuitively yet systematically explores the wide context of photography, a natural process tamed by humans. A process which, like probably any other chemical reaction on Earth, exists and which we know about because we have learned to control it and deliberately use it. Hanna is well aware of its independence from humankind and appears to have been brought to the medium of photography by her enormous interest in the phenomenon of time. As a young girl, she wanted to become an archaeologist, after all. Probably for this reason, she searches for “protophotographs”, i.e. visual recordings that originated before man “invented” the technique of photography. Probably the first known example of a negative is nothing less significant than the Shroud of Turin. Whether the Shroud is a real image of Jesus Christ or a later – medieval – artefact, most scientists nonetheless consider it to be a projection, rather than a work by human hand.

Remaking existing photographic images has become so characteristic of Hanna Råst that besides her own family album (which she doesn’t hesitate to use) and flea-market and second-hand-bookshop finds, her working archive is also often expanded by personal photos contributed by friends and students. Where does one actually find the record of an image today? What do we consider worth photographing? How much time has passed since the days when photography was an expensive quirk, when only festive family events or the last moments of a human life were recorded? And maybe the most pressing question – will our full SD cards survive us like the thin layer of silver halogenide survived the generations before us?

It is as though a photograph best mediates its content when somehow modified. Regardless whether such modification depends on partial destruction, circumstances affecting the exposure, the passing of time or the Instagram filters that imitate it, it is nothing but ironic that the processes which disrupt the original, perfectly realistic photographic record are those that make it more powerful, becoming a part of the message it carries. We strive for the sharpest macro images, and at the same time develop retro filters. Hanna, in unison with the human tendency to strive for perfection while searching for any trace of comforting imperfection, uses the best technical facilities to digitally turn her collected photographs into negatives, or cut and crease them. The exhibition, which naturally presents the results of her two month’s work, guides the visitor through a specific research spectrum. Correspondingly, the installation consists of a light-sensitive drawing carved into a white wall with a knife, a negative of the gallery floor offering a record of different footsteps and much smaller objects – castings of creased photographs, a very low relief in whose shallows we can faintly count photos pulled from an album, or a written record bordering on graphic art. Hanna Råst puts a natural emphasis on the human point of view and the significance portraiture in photography. What is more fleeting to us than our own life, reflected in the image of our face? The longing to capture oneself and those close to us became one of the main driving forces behind the boom of commercial photography. The universality and identifiability of old portraits can take us by surprise. A vintage photograph of a married couple with a child in formal clothing could depict the family history of anyone of us. The gravity and importance of preserving a person’s image can be heartbreakingly felt in the chillingly sharp “shadows” of persons burned into the pavement in Hiroshima or the period portraits of holocaust survivors, two themes that cropped up in conversation as we were preparing the exhibition. The image of these people is still clear, but their lives were ended so untimely and unnaturally. Hanna approaches these legacies without undue sentiment, by no means downplaying or denying their gravity, but able to simultaneously regard them as fascinating artefacts of a both technical and archival nature.

Through her multi-layered work, Hanna Råst explores the current status of the medium of photography in a time of instant visual content overload, while processing its historical and technical legacy. She falsifies the effects of time to get closer to the moment of origin of images that are long gone, and examines both physical remains and fading traces, with the last focusing screen being her retina. She searches for the meaning of preserved images and uses collected photographs to create her own secondary meta-archive.