Rezident

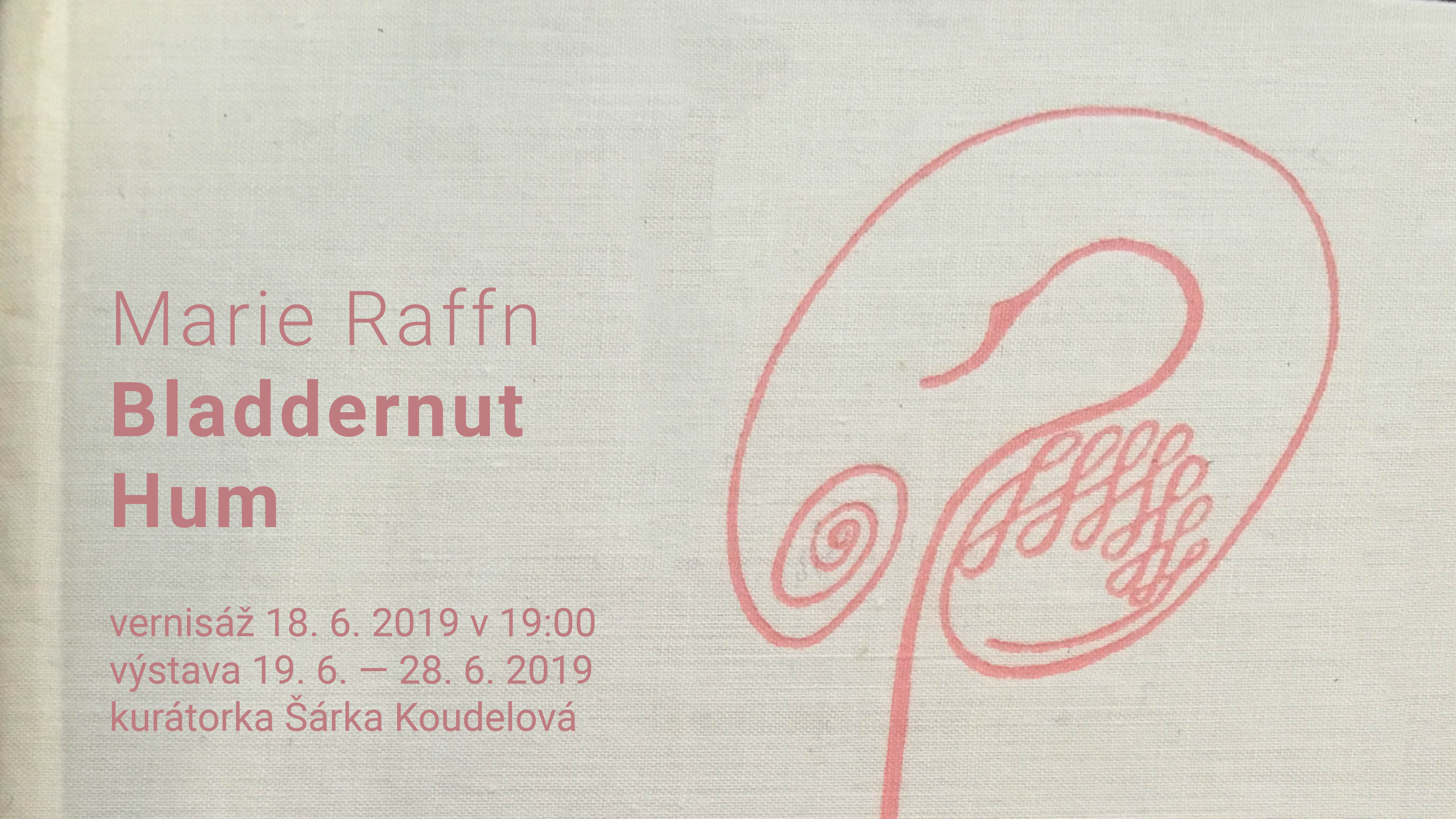

Marie Raffn: Bladdernut Hum

Fatal error: Uncaught Error: Undefined constant "fulldate" in /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-content/themes/pram/functions.php:618 Stack trace: #0 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-includes/class-wp-hook.php(324): cd_display_quote('<p><a href="htt...') #1 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-includes/plugin.php(205): WP_Hook->apply_filters('<p><a href="htt...', Array) #2 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-includes/post-template.php(256): apply_filters('the_content', '<a href="https:...') #3 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-content/themes/pram/content-page.php(20): the_content() #4 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-includes/template.php(812): require('/www/doc/www.pr...') #5 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-includes/template.php(745): load_template('/www/doc/www.pr...', false, Array) #6 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-includes/general-template.php(206): locate_template(Array, true, false, Array) #7 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-content/themes/pram/single-event-en.php(28): get_template_part('content', 'page') #8 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-includes/template-loader.php(106): include('/www/doc/www.pr...') #9 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-blog-header.php(19): require_once('/www/doc/www.pr...') #10 /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/index.php(17): require('/www/doc/www.pr...') #11 {main} thrown in /www/doc/www.pramstudio.cz/www/wp-content/themes/pram/functions.php on line 618